HuffPo’s Emily Peck ran a great Q&A with a father who wanted to use company leave benefits after his wife gave birth, but was denied. (Full disclosure: When Peck was at WSJ, she edited several posts I wrote for the paper’s site about balancing working and family.)

In the HuffPo Q&A, Josh Levs described how he was told that he was ineligible for paid caregiving leave when his third child was born. Levs said:

“There’s a vicious cycle punishing men who put family first. So many businesses reward men for just staying at the office for longer. Today’s dads are very involved at work, but the people in the C-suites are the few men who admit they don’t prioritize their family. They believe work-life conflict is a woman’s problem. They’re wrong.”

As Woman’s Work has noted before, it’s important for more men to appreciate their economic stake in caregiving. And as Levs makes clear, he and lots of other dads would like to spend more time with their little ones. A society that no longer labels caregiving as a “woman’s issue” is one that may move closer to properly valuing such work, and expanding opportunities for men and women to take the time needed to care for kids and older relatives without facing a financial shock.

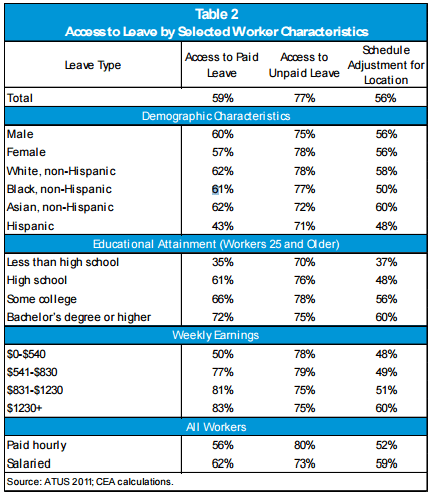

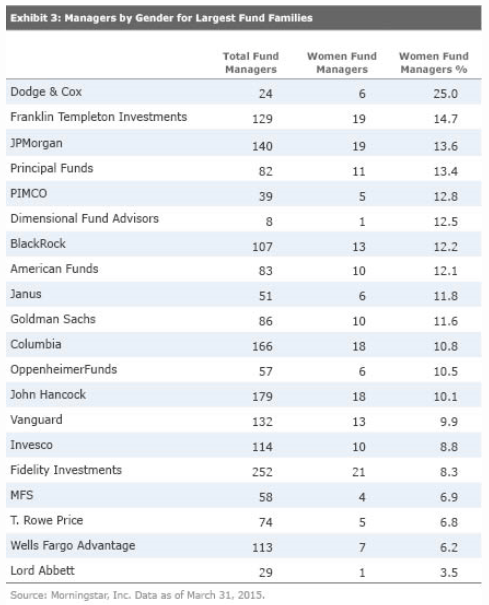

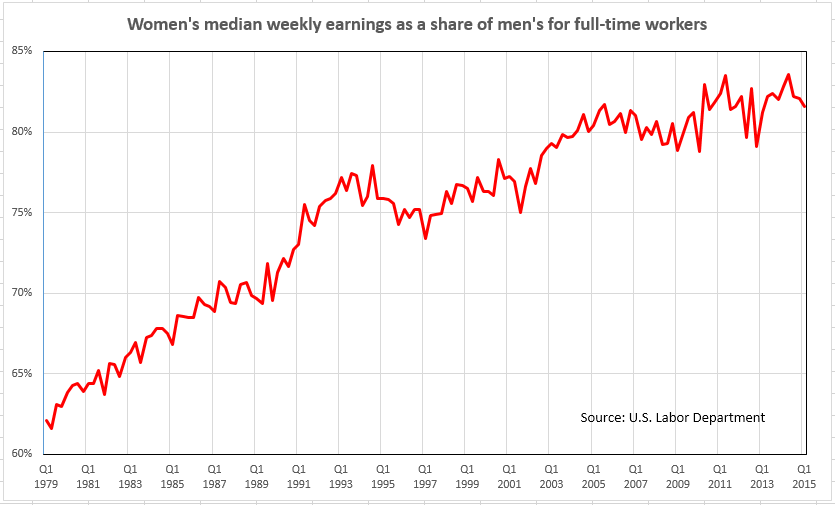

Men who can’t take advantage of company leave benefits certainly have cause for complaint. But a big-picture view of the U.S. shows an unpleasant truth: The less money you make, the less likely you are to have access to paid leave, and women are overrepresented in the most common low-wage occupations. Women of color, in particular, tend to make less than their white counterparts.

Of note, in a 2014 report on the economics of paid leave, the White House points to an interesting phenomenon: While almost four-in-10 workers say they can take some paid leave to welcome a new child, just 11% of workers are actually covered by paid leave policies.

What’s going on? The paper explains: “The gap between workers’ and employers’ reports suggests that informal arrangements with managers and the use of other forms of leave, like paid vacation, may currently be playing an important role.”

So it seems that there is employer awareness of the importance of paid leave. But companies remain wary of formalizing policies. Meanwhile, the U.S. continues to lag other major economies on mandating access to paid parental leave, but some states are supporting workers with such benefits.

–Ruth